Stanford researchers, assessing the ten most popular generative AI tools, including ChatGPT and Google’s PaLM 2, concluded that current foundation models are non-compliant with the draft EU AI Act. In particular, the researchers noted the duty that providers disclose data used to train their models was met by very few.

There are two distinct problems with this lack of transparency. The first is that much of the data curated for algorithm training is copyrighted. This raises the concern of IP theft, particularly as AI answer engines use the ingested data to divert audience, and thus, profits from content creators. If a model was truly generative, i.e., used source material to formulate original answers and views in the same manner as a student researching an academic issue, there might be a stronger fair use case. However, there is evidence to suggest that LLMs frequently scrape and reproduce pages in their entirety. For instance, when responding to a question about accommodation in Brussels, Microsoft’s AI product used content from various sources, including TripAdvisor, and prominently displayed a map of accommodation in Brussels, similar to that which TripAdvisor displays on its own website.

The second issue is more a matter of policy. LLMs currently use trillions of data points as their source material. Without a system by which verifiable fact can be sorted from fiction, AI’s answers to some questions thus inevitably pick up biases and misinformation which clearly proliferate in every corner of the internet.

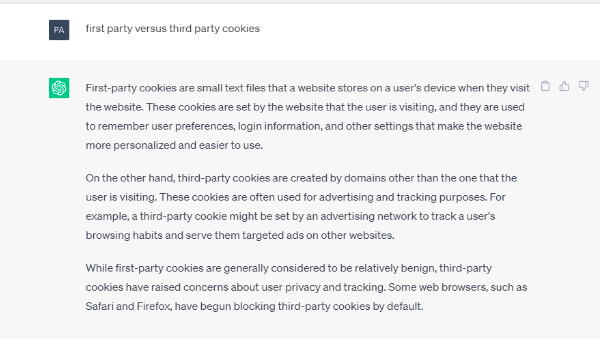

To give a very MOW example, when ChatGPT is asked the difference between first-party and third-party cookies, it describes first party cookies, entirely prosaically, as “small text files . . . that make the website more personalised and easier to use”, contrasting their “benign” function with “third-party cookies [which] have raised concerns about user privacy and tracking”. See below:

Rather than answering that both are small text files which store information, and both can be used for digital advertising, ChatGPT uncritically follows the general tenor of Google’s marketing campaigns and consequent public misunderstanding. To ChatGPT “first-party = good”, “third-party = bad”, simply because that is where the bulk of (published) public opinion lies. It is not hard to see how tools like these could reaffirm dangerous biases and misconceptions. The problem is compounded by the fact that generative AI are widely perceived to be truly clever, when in reality their strength is in pattern recognition and synthesis, which might give oftentimes, erroneous opinion a guise of legitimacy.

Foundation model providers should as a consequence be required to put in place measures to remove misinformation from the source material used to generate responses.

We notes that besides the EU’s AI Act, the issue has also been raised in the UK by the CMA. MOW will be submitting views to the relevant authorities; if you would like to add your voice, please feel free to contact [email protected].