The Information Commissioner’s Office (‘ICO’) and Competition and Markets Authority (‘CMA’) recently published a Joint Position paper, snappily entitled ‘Harmful design in digital markets: How online choice architecture practices can undermine consumer choice and control over personal information.’

The paper is an important look at Online Choice Architecture (‘OCA’), how design choices can lead to data protection and competition harms as well as some practical examples of online design choices that are potentially harmful. For a great example of what this means, please see an example of Google’s use of dark patterns in the annex at the end.

MOW agrees with most of the points raised in the paper. Firstly, as a matter of principle, MOW believes that individuals should have choice over whom they disclose their identity to as well as which consumer-facing businesses to interact with. This is also embedded within data protection legislation; consent ought to be freely given on the basis of clear, informed choices as to the risk and alternatives available.

Likewise, MOW agrees that consumers should be able to signal their preferences as to whether content and ads are personalised. As such, undermining choice through ‘dark patterns’ and ‘consent-bundling’ for services is harmful to both individuals and for competition more broadly.

As well as being a threat consumer choice and sovereignty, nudging tactics and clickwrap terms can give companies with existing market power an unfair competitive advantage in related markets. For instance, Google and Apple’s authentication services (“sign-in with Google or Apple”) or Google Pay and Apple Pay enjoy enormous advantages over competitors on account of the platforms’ unique position at the start of the user’s journey.

By the fact of owning a phone, very nearly all consumers are signed up to either service (Android and Apple account for 99% of the global OS market). This effectively disintermediates other providers of authentication platforms by force of convenience: why go through the relatively lengthy process of individually signing into a single service provider, when clicking a brightly-coloured “sign-in with Google or Apple” does the job for you?

Notwithstanding MOW’s broad agreement with the paper’s position in relation to the potentially harmful effects of consent-bundling, there are several points of emphasis where we differ.

- Firstly, MOW stresses the importance of the distinction between identity-linked data and SRB-like deidentified data, as well as the different considerations that arise between consumer-facing decisions and business-facing decisions. That is, an individual’s personalisation preferences should be regarded and treated differently than an online publisher’s monetisation of its own ad inventory using deidentified match keys.

- Secondly, and relatedly, complex business supply chains relating to data do lack transparency in relation to other business customers (see the recent CMA investigation and the US Antitrust authorities investigation into Google’s Project Poirot and Project Bernarke). However, MOW disagrees that the complexity of business supply chains is a consumer-facing issue where appropriate safeguards are in place. Where personal data is exchanged on the basis of random identifiers (as is the case for many of Google’s rivals), then there is no privacy reason why the individual needs to have control over the interoperable exchanges taking place between businesses that fund the ad-based website service being offered to their visitors. That is, a business using deidentified data linked only to an internet-connected device, but not the identity of a specific individual, should not be subject to that individual’s privacy and information rights.

- Thirdly and finally, MOW would like to highlight that the survey evidence provided in the ICO-CMA report conflicts with the survey data from Ofcom. The ICO survey found that 56% of individuals were ‘very concerned’ with how organisations collected personal information online. However, the Ofcom survey found that consumers are happy with companies’ use of identity-linked personal data (73% in 2021 and 72% in 2022 said they were “totally happy”). Given the Ofcom survey results, MOW disagrees with the Paper’s statement that individuals are routinely making ‘poor decisions’ and ‘inadvertently’ consenting to personal data processing they do not want.

At a high-level MOW agrees entirely with points and principles identified by the Joint Pposition paper in relation to OCA. The few areas of difference could, moreover, be resolved by clarifying the important distinction between identity-linked/deidentified data and consumer/business-facing challenges, as well as the survey evidence used to highlight consumers’ alleged poor decision-making when it comes to their personal data.

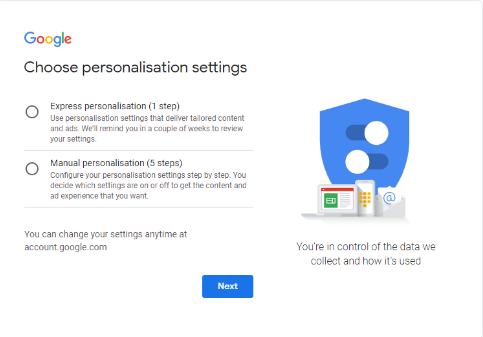

Annex: Google’s dark-patterns at sign-in

Like Meta, who were fined by the Commission for conditioning use of its services on users consenting to use of their data for advertising, Google previously forced consumers to sign-up under clickwrap terms.

Google does now give users the option to opt-out from personalisation and target advertising but it adds friction to this choice. The default setting described as “express personalisation” allows Google to deliver targeted ads and combine data sources. For consumers to restrict Google’s data processing and configure settings of their choosing, they are required to go through a five-stage process of “manual personalisation”. There is no express option by which users can declare a preference to restrict all personalisation.

This clearly encourages users to consent to extensive data processing by adding friction to alternatives but also through suggestive phrasing. Describing the default personalisation settings as “Express personalisation”, rather than “high-level personalisation”, for instance, simply confers that it is quick and easy. It is not immediately apparent that the user is giving Google extensive, fine-grained information on their online activity. Thus, by depriving consumers of a default option by which they can reject targeted advertising whilst mislabelling the choice which allows Google to track and commercialise user data, Google cleverly establish a choice architecture which encourages users to check the first box and continue.