Late November 2021 saw the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) publish two long awaited documents related to competition and privacy in digital markets. These set out important concepts relating to approaches to privacy and competition online.

The CMA’s report explained how 41 responses to a prior consultation were analysed and either incorporated into Google’s proposed Modified Commitments concerning the “Privacy Sandbox” or rejected by the CMA. Movement for an Open Web (MOW) will continue to engage in the CMA process and have published 12 initial considerations ahead of the 17th December 2021 submission deadline.

Less than 24 hours prior to the CMA, the ICO published an Opinion “Data protection and privacy expectations for online advertising proposals” addressing proposals including those from Google, LiveRamp (RampID), The Trade Desk (UID2), and a community project SWAN. The industry is now digesting the messages in these two documents.

Both documents want to help users, but they approach this objective in different ways. Queries arise from reading the documents alongside each other.

Is the ICO Opinion a final document?

The ICO Opinion was published without prior consultation. The ICO’s policy development process calls for seven stages of development, including formal consultation.[1] This raises a question: as the Opinion seems to be intended to have practical consequences, does it not require further consultation?

First parties and third parties: Is cross-domain data handling allowed if the consumer has transparently consented?

Significantly, Section 4.1 of the Opinion rejects a popular myth concerning “first party” and “third party”. This is the weak argument that who handles the data with what technology is more important than what they do with it:

“The Commissioner is aware of a view by market participants about how data protection law regards these concepts [first and third-party data]. For example, that first party has an inherently lower risk than third party. The Commissioner rejects this view.”

Usefully the Opinion also provides a simple explanation concerning the role and responsibilities of controllers under law. However, section 4.1 is in tension with section 2.2 which states “The phasing out of TPCs [Third Party Cookies] is a welcome development”.

At face value, this seems to say that TPCs can never be used by controllers despite section 4.1. It is also in tension with the UK Supreme Court decision in Lloyd v Google[2]. This found that there is no inherent harm in the operation of third-party cookies: it is all about what is done with them.

Can users consent to personalisation if Privacy-by-design features are followed?

One reading of the ICO Opinion might be that it is not possible to have pseudonymous identifiers, even if privacy-by-design features are implemented. The Opinion states:

“Identifier-based solutions … also introduce a more fundamental question about whether it is necessary, proportionate or fair for individuals to have to provide their personal data in the first place. This is particularly the case if identifier-based solutions only offer an opt-out.”[3]

However, the Opinion provides little guidance about when and why these concerns arise. There are genuine concerns about certain aspects of personalisation. For example, it is not good for people to receive higher insurance premium quotes after searching for information about personal insolvency. But these specific harms can be addressed using privacy-by-design safeguards like the network rules and resets – implementing future ICO guidance on what harms should be addressed, rather than banning the concept of personalisation. That would be a middle road, and so there are strong arguments that the Opinion does not seek to ban personalisation, but only to ensure that users can control it.

There is a significant change in how this has been addressed in the new Opinion, which approaches this as a fairness concern rather than a transparency one. There is a reference back to the 2019 Real Time Bidding report, which refers primarily to transparency concerns.[4] There are references to fairness, but these mostly concern clearly deceptive acts, like continuing to process information after consent is withdrawn.[5]

This leaves an important gap in the analysis: what happens if a transparent Privacy-by-design system collects valid consent? The starting point for UK consumer protection law is that the focus is on transparent process, not fair outcome, reflecting the difficulty in defining the latter.[6] The most recent documents from the CMA emphasise the need for transparency over data use, rather than restriction of it.[7] The GDPR refers to transparency, lawfulness, and fairness on an equal footing. It is not clear how the new Opinion balances transparency and fairness concerns.

How should the costs and benefits of different types of personalisation be weighed?

As there are different uses of personalisation, some good and some bad, it would be closed minded to assume that all personalisation should be banned. It is a little confusing, therefore, that the Opinion can in places come across as making such an assumption. Section 3.6.4 states:

‘a “universal” identifier which may in concept provide for more direct, detailed and systematic tracking than the existing ecosystem. More generally, they do not seem to remove or reduce online tracking activities and may also provide incentives for online services to increase the use of tracking walls.’

This seems to assert that “tracking” is always bad, yet there are helpful use cases of content personalisation and data handling. The CMA has noted analysis showing that as much as 70% of advertising funding derives from personalisation – and in those cases where there is no harm, there is thus a strong societal benefit (free content and access to multiple media outlets).[8]

How is harm defined?

The Opinion could be faulted for not providing a clear definition of end user harm. There is a significant difference between seeing an advert for dog food after visiting a dog food site, and the unconsented sharing of medical records. This is a reasonable distinction that should be implemented as it speaks to legitimate processing, the core concern. This is always a balancing test.

The core issue is that there are some data use cases which do not clearly engage fundamental rights. These uses should not be as strictly regulated when thinking of the “legitimacy” test. This is the inverse of treating special category data more strictly regulated under GDPR.

However, there is no guidance in the Opinion as to the specific identification of harm, as opposed to general concerns about data processing harms and the possibility of general concerns, which have been taken from a high-level ICO-wide document. This will need to be revisited.

Would data collection changes for the worse without responsible cross-domain handling?

There is growing evidence that companies are taking data collection into their own hands in response to restrictions on cross-domain data handling. What that means practically is that large scale data will simply be collected by individual businesses.[9] This “first party” data collection could apply a panoply of varying data protection policies and will not empower user control.

The same fundamental problem arises, which is the quality of the contractual terms and assent. This is the real core issue, not the question of who is doing the processing or when they are doing it: do network rules have teeth, and do they empower the user? Users can be strong or feeble in a first-party and in a third-party system – it all depends on the rules.

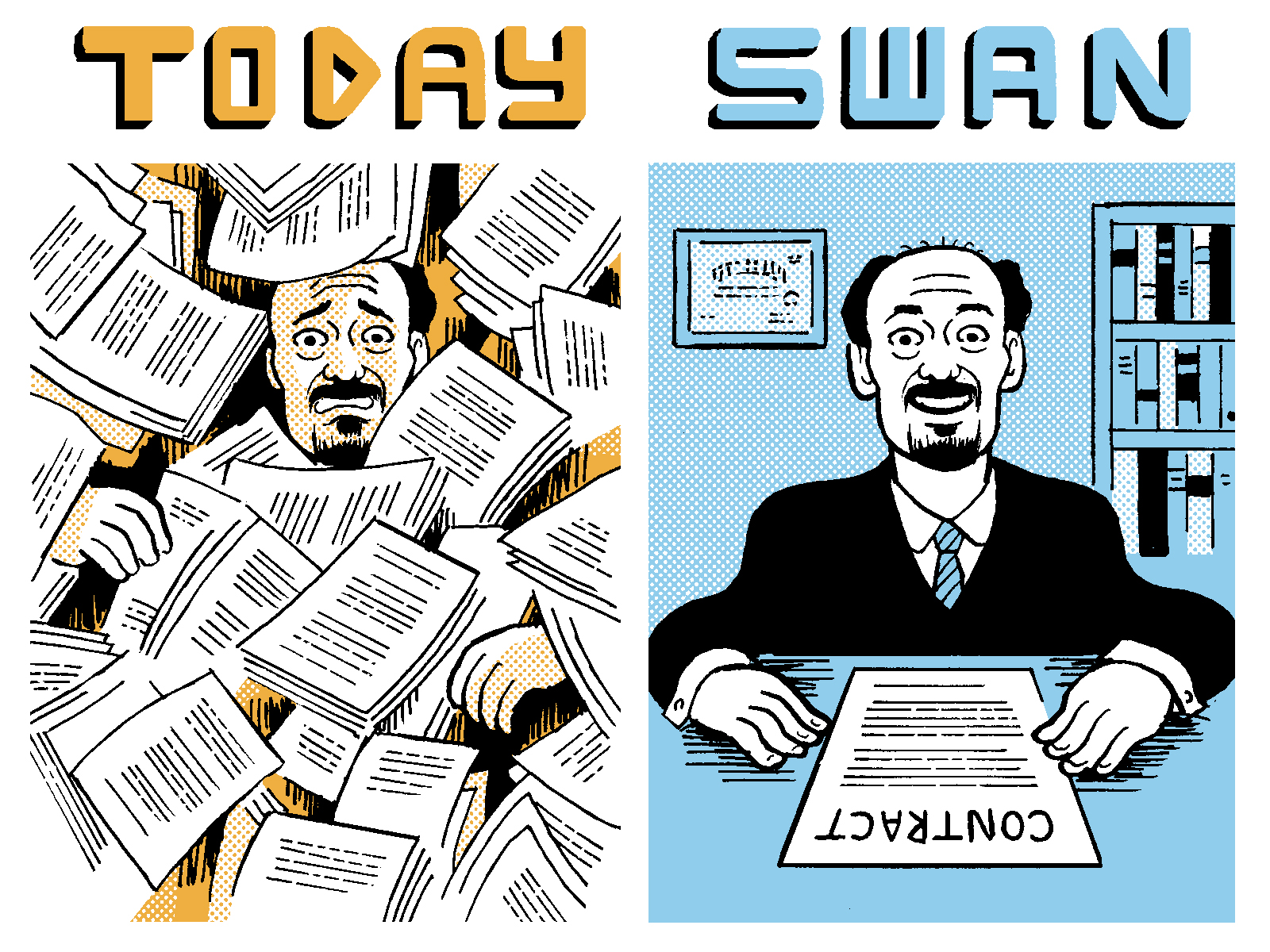

The community project SWAN presents a slide to help visualise the importance of one set of clear, comprehensible, universally applied network terms and how this can empower the user:

Do users know where all their data is?

The Opinion fudges on the first- and third-party concept, as noted above. There may be an assumption that in a first-party world, users will remember where their data is, and track these consents. But the easiest way to delete data would be to have a single reset button, and this needs a degree of cross-domain handling to work.

This saves the user the impossible task of resetting all the databases that contain identifiers and preferences. Thus, far from a risk, cross-domain handling seems to be necessary for some implementations of the right to be forgotten to work in practice. For example; the simple act of closing a private browsing window should place all the data collected beyond use. A responsible privacy-by-design identifier with a powerful reset system is likely to be the only practical way to achieve this.

What is the status of the draft Guidance project?

On 19 March 2021, the ICO’s Head of Technology Policy published a blog post Building on the data sharing code – our plans for updating our anonymisation guidance. This promises helpful guidance on Privacy-by-design standards, and the May 2021 draft guidance furthered technological neutrality by omitting reference to the “first” and “third” party distinction as a risk factor.[10]

There is a reference to the May 2021 draft Guidance in the Opinion, but all that the Opinion says is that it requires “organisations to consider identifiability risk” (fn 82). But this is simply a generic statement of data protection law, and it does not provide any guidance on how the two documents interact.

This Guidance document draft was subject to formal consultation, unlike the Opinion. The period for comment closed on the Sunday after the Thursday when the new Opinion was published – Thanksgiving weekend. There will be a need to revisit comments on the new guidance and to extend the comment period to ensure due process to ensure Equality Act 2010 compliance as well.

Thinking of the competition law angle, requiring all internet gatekeepers to facilitate and not interfere with the implementation of properly consulted on Guidance may well represent the most effective remedy of those currently contemplated by the CMA.

How does the Opinion address CMA concerns about large technology providers gathering inadequate consents?

The CMA commitments consultation lists competition concerns over personal data collection. The CMA states that it is concerned that Google’s conduct, specifically in regards to, Privacy Sandbox will cause:

“…potential harm to Chrome web users through the imposition of unfair terms.”[11]

The two commitments proposals have specified this concern in different ways, and there is debate as to whether the new commitments package fully addresses the stated concerns given some limiting language in the latest draft. This is especially striking as the CMA has raised further concerns as recently as 14 December 2021 in the Interim Report the CMA published in its Mobile Ecosystems Market Study. This raises significant concerns about anti-competitive browser design decisions:[12]

“There are material barriers to competition in browsers resulting from… Apple and Google influencing user behaviour through choice architecture, including in particular pre-installation and default settings.”[13]

Footnote 416 states: “Tracking of users’ activity is often invisible to users, and their consent is not always sought, or sought in a way that does not comply with the requirements of data protection and privacy law.”

This frames the issue as one of a lack of transparency from large data processors. It does not say that the concern is who does it, nor does it argue against trading data for content, but instead focuses on the transparency of what was done so that users can choose.

There is helpful language in the ICO Opinion that aligns with addressing this concern:

“The Commissioner reiterates that data protection law places obligations on the entity or entities that determine the purposes and means of the processing of personal data…

This is the case regardless of where the controller sources the personal data… and whether the controller is a large technology platform with multiple services, or a single organisation that seeks to share personal data with other organisations.”[14]

This helpfully notes that whatever the transparency, lawfulness and fairness concerns are, they apply equally to large and small firms.

However, the ICO’s point does not directly answer the concern expressed by the CMA. This is broader than just formal equality of treatment and a lack of formal discrimination in data protection law – important though that also is. The major concern relates to the large number of touch points that large platforms have, creating an incentive to impose over-broad, unfair privacy terms. An academic study found that Google has trackers on as many as 75% of the top million Internet websites.[15] This is the substantive cause of the concern about excessive data collection: a web-wide system of trackers which can be called “first party” to Google despite very little, if any, user transparency.

In 2004, Google’s privacy policy added a broad right to cross-domain data handling:

“If you have an account, we may share the information submitted under your account among all of our services in order to provide you with a seamless experience and to improve the quality of our services.”[16]

This finds expression in the current Privacy Policy as follows:

“The information we collect includes unique identifiers, browser type and settings, device type and settings, operating system, mobile network information including carrier name and phone number, and application version number. We also collect information about the interaction of your apps, browsers, and devices with our services, including IP address, crash reports, system activity, and the date, time, and referrer URL of your request…

We’ll share personal information outside of Google when we have your consent. We’ll ask for your explicit consent to share any sensitive personal information [i.e., non-sensitive data can be shared on the basis of a general and open-ended consent]…

We provide personal information to our affiliates and other trusted businesses or persons to process it for us, based on our instructions and in compliance with our Privacy Policy and any other appropriate confidentiality and security measures.”[17]

Creating meaningful competition.

What is needed to address this exploitation concern is competitive constraint to drive competition over data handling. Without this, it is the famous “level playing field,” but without a “match being played” on it.

It is not enough just for the rules to be “non-discriminatory”. Otherwise, Google can cut off access to data including to itself and state (accurately) that there is a “level playing field” without fixing the underlying problem, which is about the quality of “play on the field”.

To align the ICO and CMA analysis, there needs to be specific attention to the concern about large systems applying a one-size-fits-all consent, to ensure that responsible innovators with Privacy-by-design systems are not squeezed out by over-broad consents. Otherwise, that harm will go unaddressed, as Google can point to DPA compliance under the Commitments as currently drafted.[18]

Due process.

The Opinion references alternative proposals, all of which it considers, to be deficient without providing useful explanation. This leaves the reader wondering if an alternative proposal falls short in one minor area, or in all areas? For example, p.7 refers to the Google Privacy Sandbox as a set of proposals without providing any detail on what aspects of the proposals do or do not raise concerns. This provides no guidance.

In relation to SWAN the ICO miss important unique factors. SWAN is a rules-based “data trust” to avoid conflicts of interest and protect users from commercial exploitation. SWAN, including the open-source code on which it is based, is stewarded in the interests of users, not shareholders. Governance follows the economic principles for common resource management established by Ostrom. The advocates of SWAN provided the ICO a detailed analysis concerning the features SWAN contains to answer the challenges laid down in the 2019 report. These factors are highly relevant and materially impact the way analysis should have been conducted.

As such the validity of the Opinion is questionable.

The CMA and ICO apply different laws.

It is helpful that the Opinion does not rule out exploitation of user consent by large companies as a possible concern, but specific guidance would be much appreciated as to how the imposition of unfair terms concern from the CMA interacts legally with the ICO, so as to bridge the gap: a ban on abusive exploitation at the CMA but a requirement for fairness, transparency and legality at the ICO.

The Opinion contains the sharp statement that, while there are overlapping aims at the ICO and CMA, “the objectives of data protection and competition law are not ‘tradeable.’”[19] This seems to backtrack on the green shoots from earlier co-operation, which seemed poised to develop a shared position on concepts like “informed decision making” and “real choice” for users.[20]

Significantly, the CMA’s new Mobile Ecosystems Interim Report suggests that this dialogue did not survive the winter: the CMA “will seek to engage with the ICO” (after this major publication) to assess whether pro-competitive interventions are possible – a much narrower scope of discussion than that of six months ago.[21]

Specific guidance on how the two sets of legal tests interact could be framed to address the CMA’s concern about harm to competition from poor consents from Google, while also maintaining DPA neutrality between large and small companies as the ICO Opinion seeks. This would help answer the essential question: how is meaningful choice to be achieved, empowering the user while still preserving the value from complex supply chains?

Is it safe to rely on the W3C for data protection standards development?

MOW has long been concerned with the role of the W3C standards body in facilitating collaboration among web browsers for the benefit of Google and Apple. MOW wrote to the CMA, US Department of Justice, and European Commission providing evidence on 2nd December 2021.

Section 3.7 of the Opinion references the W3C’s “Self-Review Questionnaire: Security and Privacy”. But this document does not once recognise the privacy role of controllers, processors, or any of the other privacy concepts described in section 4 of the Opinion. It is also unclear how the ICO is represented at the W3C to ensure compliance with UK law (e.g. due process requirements). It is hoped that this can be clarified, to avoid the impression that the ICO is getting the W3C to do its homework.

The W3C is a puzzling choice in the context of concerns shared by the ICO and CMA that large technology companies should both face the same rules, and specific CMA concerns that Google could use Chrome to apply unfair data terms. Google has a lavish 106 representatives at the W3C, whereas most of the c.450 members have just one, and many participants are not represented at all.

Google has been fined repeatedly for data protection issues. No reason is given to justify the use of a Google-dominated standards body as the appropriate forum for the outsourcing of data protection principles – if that is even allowed in the first place. One might well share the concerns voiced by Privacy International “On the hypocrisy of using privacy to justify unfair competition”. There would seem to be risks in allowing big tech to define privacy.

The need for technologically and party neutral guidance.

Other sections in the report reference the W3C but provide footnotes that do not link to W3C documents but instead a private individual who works for Apple (fn 100). This is confusing as it is unclear what the status of the document is.

This may not be necessary: the purpose of regulatory guidance is to provide statements of concerns, costs, and benefits for society at large, rather than the specific implementation of those principles in standards. The issue with the W3C can be avoided if the future draft Guidance backs up a step and states what those concerns are and how to weigh them up, rather than getting into the detail of particular comments from particular employees.

There are some important factual inaccuracies which depart from the record.

Section 3.6 of the ICO Opinion contains inaccuracies when referencing alternative proposals. Some examples include:

- Footnote 83 in relation to the SWAN project leads the reader to conclude the email address is widely shared by the system. This is not accurate. It ignores an important privacy-by-design feature of SWAN, which is explained in the relevant reference document which states “[Email] can not be made available [to] any other party or used for any other purpose [than allowing the user to edit their email address].”

- Footnote 84 goes on to reference a document from Mozilla titled “Comments on SWAN and Unified ID 2.0” which at section 3.5 states “SWAN allocates a single pseudonymous identifier to a user”. SWAN creates an identifier for a web browser, and not a user. SWAN holds a separate and optional identifier for the user.

A stale debate about 1997 cookie specifications.

A case in point is the emphasis on the Internet Engineering Task Force’s (IETF) Request for Comment (RFC) 2109, also known as a technical standard for cookies. Published in 1997, this was always thought to be a little ambiguous because it seemed to place limits on cross-domain handling.[22] However, it was largely ignored by web browser implementors and regulators for decades. This oversight played an oversized role in Google becoming Google, Facebook becoming Meta, and the dotcom boom and all the history since.

But this is not really an interesting, much less the contemporary, point. It is of interest to a select few experts, but to others the point is simply a mystery. Rather than digging up the archaeology of the internet, it seems wise to keep eyes on the road ahead. In this case, it would be helpful to identify the principled concerns about harmful instances of cross-domain data handling that distinguish them from the helpful ones, and to specify these in terms of controller and process as advocated in section 4.1 of the Opinion, rather than to debate the fate of a 1997 standard.

This point is especially acute because the CMA’s modified commitments document also refer to the W3C and tacitly endorse Google and other web browser vendors implementing de facto standards, despite difficulties in the development of competitively neutral standards at the W3C and IETF[23].

Conclusion

It is clear from the documents that all involved are acting in good faith and trying to deliver a world where users have greater control over all personal data linked to their identity, while also gaining the benefits from online services. Predictably, there is an issue in that this means different things to different people active in the debates.

Everyone wants to put the user in the driving seat, and given time, they will get there. There will however be a few more rounds of comment, presentation, and debate, about the best route to take.

[1] ICO, Regulatory Policy Methodology Framework. “Formal consultation should be used once you have developed your analysis and evidence sufficiently to articulate the range of potential policy options.” (p.31).

[2] Lloyd v Google LLC [2021] UKSC 50. See e.g. para 153, which points out that there was no clear evidence of user harm to users just from the deployment of third party cookies for advertising.

[4] ICO, Update report into adtech and real time bidding (“2019 RTB Report”), p.19.

[5] 2019 RTB report, p.19

[6] s.62 Consumer Rights Act 2015 (no jurisdiction over fairness of price provided that the price is clear); Regulation 6, Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 2008 (information to be provided to allow the average consumer to make an informed choice).

[7] CMA, Mobile ecosystems interim report, 14 December 2021, fn.416 at p.249 (stating a concern about inadequate consents and opaque tracking).

[8] CMA, Final Report into Online Platforms and Digital Advertising, para. 44. The ICO argues that competition and data protection are not “tradeable” (section 4) but this is seems slightly wide of the mark unless there is first a demonstration that there is a genuine fundamental rights issue – otherwise, the competition is lost, thereby harming the service user, without a genuine privacy concern in play. The situation is very different of course if there is a fundamental right, and these are not tradeable – but they need first to be defined.

[9] WSJ – Big Tech Privacy Moves Spur Companies to Amass Customer Data

[10] ICO, Draft anonymisation, pseudonymisation and privacy enhancing technologies guidance

[11] CMA, Consultation on commitments in respect of Google’s ‘Privacy Sandbox’ browser changes, consultation on first Draft commitment (June 2021) (3.24); but compare CMA, s, Modified draft commitment (Nov 2021) 2.3(c), p.9 describing only a subset of the original concerns.

[12] Section 5, Competition in the supply of Mobile Browsers. See especially Using browsers to reinforce or strengthen a market position in relation to other activities (pp. 244-253).

[13] CMA Mobile Ecosystems Interim Report, 5.150.

[15] Englehardt and Narayanan, Princeton University WebTAP project, ”Online tracking: A 1-million-site measurement and analysis.”

[16] New York Times, The Privacy Project, Google’s 4,000 word Privacy Policy is a Secret History of the Internet

[17] Google Sharing Your Information

[18] C.8.(a): “impact on privacy outcomes and compliance with data protection principles as set out in the Applicable Data Protection Legislation” as one of the Development and Implementation Criteria.

[20] Competition and data protection in digital markets: a joint statement between the CMA and the ICO, 19 May 2021, pp.26-27.

[21] Mobile Ecosystems Interim Report, 5.226. Emphasis added.

[22] RFC 2019 4.3.5 – “When it makes an unverifiable transaction, a user agent must enable a session only if a cookie with a domain attribute D was sent or received in its origin transaction, such that the host name in the Request-URI of the unverifiable transaction domain-matches D.”

[23] For example; HTTP Client Hints which are now being widely deployed by Google is defined as a Non-Standards Track Maturity Levels Experimental RFC at IETF meaning “The “Experimental” designation typically denotes a specification that is part of some research or development effort. Such a specification is published for the general information of the Internet technical community and as an archival record of the work, subject only to editorial considerations and to verification that there has been adequate coordination with the standards process (see below). An Experimental specification may be the output of an organized Internet research effort (e.g., a Research Group of the IRTF), an IETF Working Group, or it may be an individual contribution.”